But when she heard lamentation and wailing from

the Wall, her limbs quivered and the shuttle fell to

the ground out of her hand.

The Iliad, Book XXII, Homer

Art in Public Places

The idea of Public Art is intrinsically linked to a concept of Public Space. Furthermore the presence of art renders Public Space, formal or otherwise, as Civic Art, the highest form of spatial expression in the building of community. The public realm in our cities varies functionally and programmatically, from the ordinary and the utilitarian to the emblematic and representative, but what is true and unequivocal is that the private realm is the realm of our daily lives, Alltagsgeschichte, and the public realm is instead, where in human settlement, the collective consciousness of ourselves as society is manifest. Public Art, its place and purpose, shares a common past and fate with the history and prospect of the public realm in the city since its conception and remains today a critical dimension in how public space is perceived and defined in contemporary communal life.

“At the dawn of history, a city was not primarily a place where people lived, but a meeting place where people assembled, for trade for worship or for military purposes.” We assume as well, with reason, that the enigmatic and wondrous images of animals and people, “scratched and painted on the walls”(1) and ceilings in the interior darkness of caves are associated with ritual and magic, and with a place of gathering in communion for a common, pious purpose. The paintings are crafted and composed with intention, it seems, and in consideration of a distinct setting. The descriptive scenes of the thrill of the hunt, of “the everyday” life in the village, the clamoring of hands in congregation (Fig 1), are drawn to project an impression of movement, ”like the frames of an animated movie”, (2) seen from the flickering light of a torch against the undulating walls in the unending night of the cave.

“Mid the uneasy wanderings of Paleolithic man, the dead were the first to have a permanent dwelling” Night and day, “the powerful images of daylight fantasy and nightly dream” (3), are metaphors of life and death and the place – realm is the object of memory , the impulse for the eternal return of the living. In the early history of Rome, an initial instance of communal life was in the shallow between the Palatine hill and the Capitoline, a necropolis, which in time evolves into the Forum, the very center of Civic life of the city. The critical performance of the public domain in antiquity is in evidence in the artifacts and places of the archeology of the city as well as in the theory of planning and building in written treatises.

The Rome of Marcus Vitruvius Polio, the author of The Ten Books of Architecture, the one remaining treatise on Architecture from antiquity in the western tradition, is a city under construction. Like no other city perhaps, Rome is a city characterized by a sequence of deliberately built public communal spaces, the domestic program occupying, unceremoniously, the amorphous space in between the formal communal meeting places, many of which, in the millenarian history of the city, have retained a public collective content to our days. (4)The treatise, which can be read as a practical manual of architecture and city building given the circumstances, is concerned with discerning between the fundamental functions in the experience of the city by its inhabitants, in the case of Rome, the civis, or citizenry.

Early in the treatise, in Book I in fact, after accounting for the education of the architect as an Ars et Sciencias curriculum and reciting the fundamental principles of architecture, Vitruvius defines what architecture consists of, “ The parts of Architecture itself are three: Building, Dialing and Mechanics. Building in turn is divided into two parts; “of which one is the placing of city walls, and of public buildings on public sites; the other is the setting out of private buildings“. (5) By this explanation the city, and its essential life experience constituent components, is prescribed. “There are three classes of public buildings”, he continuous, ”the first for defensive, the second for religious, and the third for utilitarian purposes.” (6)

Walls are deserving of a specific denomination in the author’s mind, and rightly so. In the history of human settlement, prevalently, parametric walls, forming the boundary of a closed geometric figure, have been amongst the greatest investment of infrastructure, in labor and treasure. Where they remain today, despite their original function being defunct, the infrastructural contribution remains dauntless, as are the Aurelian and Servian walls of Rome, the greatest of the extant monuments from antiquity of the city, or the haunting memory of the walls of Beijing,

which stood intact practically until the mid XX Century. For city walls served not merely a military and defensive purpose but were, to its inhabitants, a source of pride and identity reflected in the public buildings of the city. The defined space within and at the edge of wilderness, constituted the political, and economic space-realm of community, where the sacred and the profane coincided in social public life. It would have been what the traveler saw from the distance initially, in the approach to the city, profiled against the mountain or the sky, the first sight of home and the first testimony of the collective aspirations of the city. Virtuous Gilgamesh, the ruler king, is the builder of walls, the builder of cities as he is wise and skillful.

“…, Go up and walk on the walls of Uruk,

Inspect the base terrace, examine the brickwork:

Is not the brickwork of burnt brick?

Did not the Seven Sages lay its foundation” (Epic of Gilgamesh)

“The Gods being fickle and heartless, the city thus affords all the immortality that human beings can attain” (7). Expressed in its walls, temples and utilitarian structures is the Ethos of the city and thus the very character of its people. By “utilitarian purposes” Vitruvius refers to the general “provision of meeting places for public use”, such as harbours, markets, colonnades, theatres, promenades and all other similar arrangements for the foreseen use of the public. The walls, meeting places and temples of the city of antiquity constitute, what we today consider as infrastructure, meaning a fundamental constitutional framework and, in the case of the city, the basic physical and organizational structures and facilities fundamental for the operation of a society. It is worth noting, because of the machine as protagonist in our individual and collective lives today, the inclusion in the treatise as a disciplinary consideration of “Mechanics”, or machinery, depending on the translation of the Latin word machinatio, as part and parcel of a classical conception of the city.

In the following passage in Book I, Vitruvius describes the criteria to be satisfied in the evaluation of buildings, a criteria of critical worth to the artist of the Renaissance and regarded as of value to this day. “All these must be built with due reference to Durability, Convenience and Beauty “. (8) No distinction is made, in terms of satisfying these three criteria, between the house, the temple and the infrastructure of the city, between the Public and the Private Realms. It is not possible to imagine from this text, the probability of a city in the absence of these corresponding realms, nor to consider even a hierarchy between the two where, one is merely “convenient ” and the other, somehow, exclusively ” beautiful”. The convention in contemporary city planning theory, of segregating the parts of the city into singular and limited functions deserving to different degrees of qualitative engagement, simply does not exist in antiquity, at a time when the city had a greater meaning and significance to the “individual and collectivity alike”. (9)

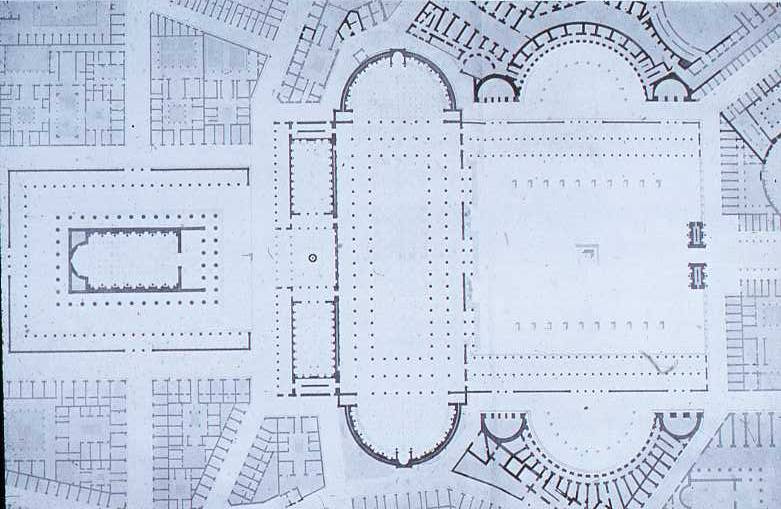

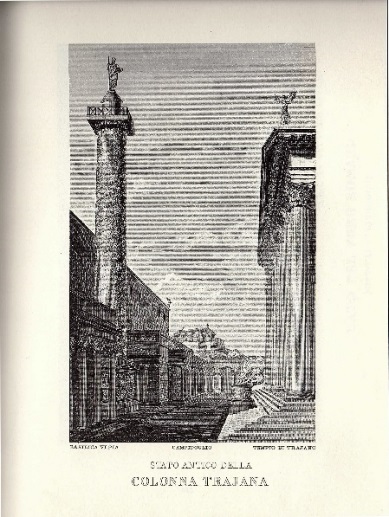

Vitruvius would not see the eventual Rome of Trajan but the lessons from Book I are very much in evidence one hundred years or so after his lifetime in the construction of the public infrastructural projects for the expansion of the city unto the low lying fields of the Campo Marzio. The construction of the Forum of Trajan,(Fig 2) the last and largest of the imperial fora in Rome, and the markets, is a remarkable Urban Design project which involved excavation and retention of the adjacent hills to the site. The markets, built “to make amends for the demolition of many shops during the land-clearing for Trajan’s Forum” are but one of the compositionally conceived collection of buildings of distinct natures and serving different functions. (10) The utility of the markets and the civility of the forum are considered as one with the “civil engineering” and infrastructural exigencies of the work. Apollodorus of Damascus, the supervisor of the works, “was by training an engineer as well as architect, if indeed such a distinction would have been meaningful in classical Rome” (11) is as able with the infrastructural content of the project as with the architecture and the lyrical expressive content of the work as art. The column of Trajan placed in between a Latin and a Greek library, shaped as an upright scroll, is a compelling formal device. The continuous helical frieze rising from base to capital, was in “its time an architectural innovation”. As much for the singular but yet familiar shape and scale of the column, as for the placement of the sculpture in a public space pressed against the street, the” idle passer-by” cannot but be impressed by the modulation of the urban space and the art-quality of the piece itself. (Fig 3) Trajan’s Column has the characteristics of “intentional art”, and despite its commemorative value as a monument, what remains meaningful as a ruin artifact, rather than its historical value, is its art value as a sculpture in a public space. (12) From a Tendentious, perspective, the primary purpose of the monument, a designation which shares a common etymological origin with the word memory in the Latin word monere, is admonishment, to remind, and thus to memorialize in time an event or person of collective significance to a society in a present or future tense.

Today the column stands alone nominally intact amongst the ruins of the foro Trajano, the faded stone reliefs glistening against the mute terracotta tones of the exposed brick work of the market, itself a hallowed shell. The commemorative content of what was originally built as an art-monument is diminished and its value as a work of art enhanced. (Fig. 4) The miraculous survival of the column through the middle ages, when the harvesting of materials from the spoils of antiquity for practical necessity was commonplace, is due to a lingering longing for the power and grandeur of the past, on the one hand, “a sentiment not quite lost to the medieval Roman”, but also, in XV Century Italy at least, “because of an increasing appreciation of the artistic and historical value” of the until then languishing mysterious and enigmatic ruin. (13) The column was for centuries buried in the informality of the domestic fabric of medieval Rome, a Rome built upon the foundations of the ancient city, devoid of its public space – realm, the libraries, the forum and the markets in ruins. Not until the early XVI Century, when the artistic and historical value associated with ancient art promotes significant measures for the reservation of monuments, does the column begin to recover its public space, eventually in the form of an archeological setting.

Disinterred and excavated the ruin is where, in building artifacts, the last memory resides. Ruins reveal the foundational and infrastructural characteristics of what once was, in a way not evident to the eye while the building is “alive”, and recovers in silence, the spatial and volumetric constitution of the building and urban construct, originally conceived and built as public space.

“As if these ruins were not enough, as if man could go no further before

heaven till he exhausted the physical round of his own mortality in the

obscure cities hidden in the ageing world”.

(Allan Ginzburg, “Siesta in Xbalba”)

With the demise and ruin of the city after the gradual but inevitable collapse of the “gesta municipalia”, in the early middle ages in Europe, Public Space and thus Public Art as such, survived physically, if at all, as incomprehensible vestiges of a past not remembered, and would not emerge again as integral to community until the recovery of the very idea of city in the XII Century. The return of communal organizations and a burgeoning middle- class, both of which are “fundamental attributes of the city in modern times.”, (14) would create the conditions for the necessity of the collective public “space” and recover the classical conception of city as consisting of Public and the Private realms. “Primitive though it may be, every stable society feels the need of providing its members with centers of assembly, or meeting places.” (15), In the street and block configuration of countless new and old Burgs, the old, remnants from antiquity, the newly founded spring along alternative land trade routes to the East, is a dedicated realm to the collectivity.

As with the city state in antiquity, the structure of governance of the Comunes, democratic or not, served a social political psychology in the citizenry which depended on the manifestation and function of a public collective space. “Observance of religious rites, maintenance of markets and political and judicial gatherings necessarily bring about the designation of localities intended for the assembly of those who wish to participate or who must participate therein.”Generally secular and sponsored by trade guilds and civil associations, Public Space had as a stated purpose the celebration of the collectivity and the enhancement of public life. Also as in the Polis, and Urbs for that matter, the embellishment of the public realm through art in the mediaeval town is a common practice and pursued with zeal. “ The functions of the agora or forum on the one hand and the market place on the other were maintained as was the desire to unite outstanding buildings at these major points in the city and to embellish these proud centers of the community with fountains, monuments, statues, other works of art and tokens of historic fame. Plazas decorated in this sumptuous manner were still the pride and joy of the independent towns of the middle ages and renaissance.” (16)These are the piazze, Plätze and commons which we recognize today to be the physical embodiment of collective civic life in the history of cities; beautiful, in a classic sense, unto themselves as public art.

The promotional value of the public square in urban design rest on the legitimacy of the public realm as an essential constituent component of what can be determined as city, as it is manifest, in the west at least, in city building practice and theory in antiquity and recovered by the comunes in the 11th and 12th centuries in Medieval Europe. In the Renaissance in Italy,“ when historical value was first recognized ” (17) in the fragments and artifacts of a civilization in ruins, the public square is re- invented as a work of art and planned and built accordingly. The demonstrative quality of time in the unplanned square, built organically and empirically through the centuries, is a secondary consideration. What the invented public square lacks in authenticity, devoid as it is of the meaning inherent in the imposition of the passing of time on urban form, it gains in consonance and coherence in the form and shape of a distinct geometric figure. The trans- figurative urban design interventions in the Rome of the cinquecento are just such inventions. Despite the fact that the “new squares” share foundational infrastructure of historico- cultural significant sites and even remains of buildings, lost and forgotten, they are, for all practical purposes, at the time, new building sites , formally and conceptually. The collective quality and psychology of the new public realm is chiseled further by the cultural- political program inherent in the public civic space considered as a work of art, fabricated in an instance as a singular gesture and imbued with clarity of purpose.

While in the Piazza della Signoria, the civic and political center of the Florence, the statue of the David by Michelangelo, placed as it was, off symmetry, its smooth marble finish contrasting against the rusticity of the stone work of the Palazzo Vecchio, its head turned slightly towards the river with a contorted glare in the direction of Rome, the Goliath, culminates, in a sense, the aesthetic composition, and narrative program, of the urban space. (Fig 5) The square, built over time, is inconceivable by the XVI Century to comprehend spatially devoid of the Statue.

“The pose of the statue may seem arbitrary and easy,

How long the figure must stare after the piazza is empty

(Burns)

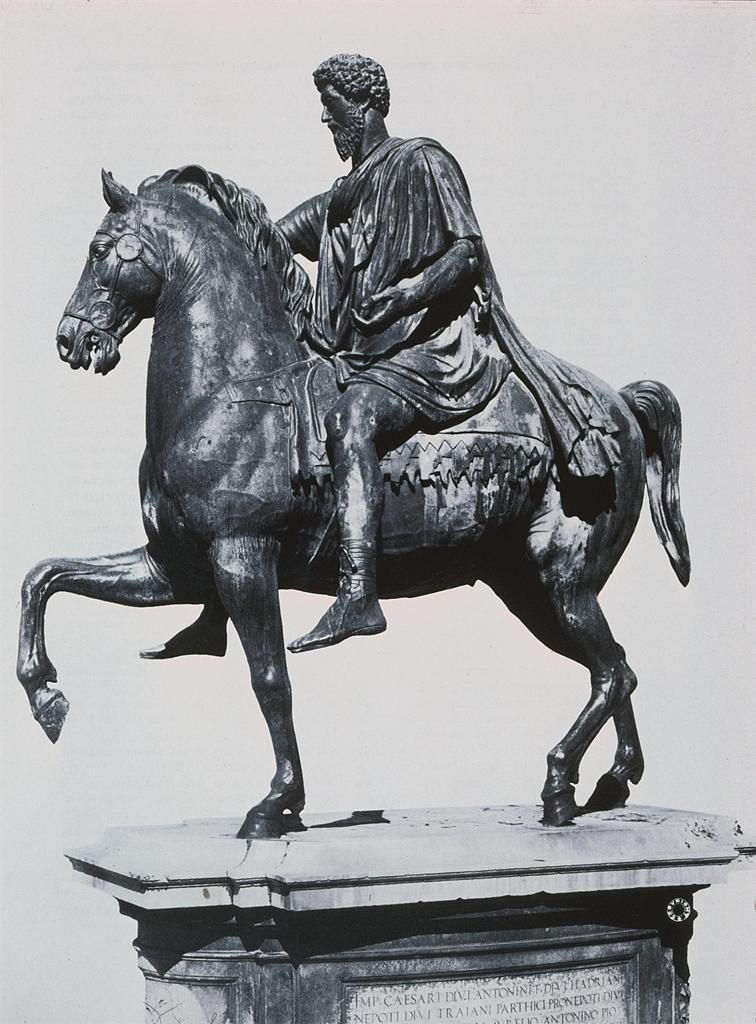

In Rome, by contrast, in the conception and eventual construction of the Piazza del Campidoglio the statue “was not merely set into the piazza but inspired its very shape.” (18) In the Campidoglio the statue is the “inaugural” piece in the “invention” of what would become amongst the most extraordinary civic realms ever built, thematically and, most importantly, formally. The bronze equestrian statue of Marcus Aurelius(Fig 6) dating from antiquity, was admired technologically as an excellently crafted work of cast bronze and, in the minds of both patron and artist, as a work of art. Moved to the site by Pope Paul III and placed more or less in the center of the then unruly and unleveled plain atop the Capitoline hill, For Michelangelo, a sculptor himself, the use of a “found piece”, of that kind and quality, as a center piece sufficed for the configuration of a new square that would serve in practical and symbolic terms the secular governance of the city. Considered as an integral composition departing from the bronze statue at its center, the geometry of the space, the flanking buildings, the decorative program, the sequence of events are conceived and implemented as a work of art and as such, most eloquent of the civic nature of the space.

Beyond the artistic attributes of the sculpture, the figure of Marcus Aurelius was a symbol of civic virtue and represented in Humanist thought the “ideal emperor, exemplum virtutis, peace maker dispenser of justice and Maecenas.” (19) His wittings on virtue and dutiful behavior, written as personal notes but eventually published as the Meditations were a guide to personal duty and civic engagement. For Pope Paul III the selection of the statue and the effort to transport it to the civil administrative realm of the city on the Capitoline Hill as the focal point for the design of a “new” public space provided a perceived continuity of virtuous rule. To the architect artist of the time, the building of the city is considered an entirely civic activity. To Leon Batista Alberti, whose treatise on architecture, De Re Aedificatora, recovers the Vitruvian commitment to the building of the city, the validity of the embellishment of the city through art is justified and its value measured to the extent “it is able to bring glory to the city in utility and ornament.”(Blunt) In the mind of the “Philosopher Urbanist “, Art and Architecture would contribute to the edification of the Public Space as fundamentally Civic in nature and imbued, in the models of the Renaissance, with a compelling beauty and inherent meaning.

The invented public realm as art space and manifestation of civic virtue, fictional or not, would become the prevalent criteria for countless urban design interventions in the founding, expansion, beautification and refurbishing of cities for centuries to come, all over the world. The reconstituted fabric of the Baroque period, the squares of the enlightenment, the founding of cities like St Petersburg on in the delta of the river Neva, the modernization of London in the 18th Century and the city at the advent of the new republic, all share in common the concept of urbanism as public art. In America, the 19th Century is book ended by the master plan for the “instant city”, sited by Washington and Jefferson and planned by the French –American, military engineer educated in the Royal Academy in the Louvre, Pierre Charles L’Enfant in 1791 and the Plan of Chicago by Burnham and Bennett, commissioned by The Commercial Club and presented to the public in 1909. Both plans are exemplary models of urbanism as art and civic consciousness and would nourish the thinking and building of towns and cities across the country.

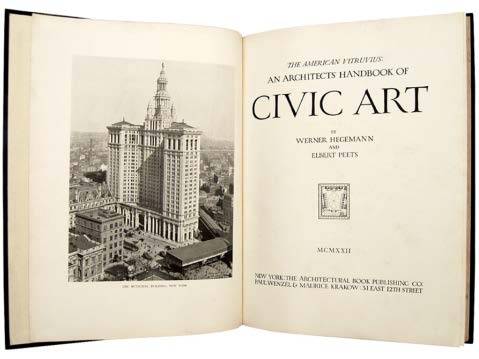

And yet by 1920, the urbanist Werner Hegemann and landscape architect Elbert Peets felt compelled, to publish a book titled The American Vitruvius, An Architects’ Handbook of Civic Art, where the protagonism capacity of Art in the definition of cities, in particular the articulation of the public realm, would be reconsidered and proposed as the only constructive prospect to address the informal chaos and dysfunction of the capitalist “speculative city “.(Fig 7) “Against chaos and anarchy in architecture emphasis must be placed upon the ideal of civic art and the civilized city” ( Hegemann and Peets). (20)

The book, which is a compilation, a “thesaurus” of a kind, of models in civic art, promotes unambiguously the classical ideal associated with the Vitruvian tradition “and the greatest of those ideals, though in these days of superficial individualism is often forgotten, is that the fundamental unit of design in architecture is not the separate building but the whole city.” (21) The over one thousand illustrations in the book, selected from different continents and time frame, “an atlas for imaginary traveling”, share a formal character in shape and form of a figural nature. In other words, the collection of memorable instances of Civic Art in history could be recognized first and foremost as a geometric figure inserted meticulously and with determination in the cityscape or landscape. A conception of art and space which would disappear within the imagination locks of the modern movement and its naïve theoretical formulation of the city, on the one hand, and lost in the intrinsic limitations, and ultimately inability, of the physical figure to address the social priorities of the inexorable change of modern society in the XX Century.

In the age of social “mass mobilization”, In the United States and the Soviet Union, as examples, for altogether different reasons and antecedents, public art projects were sponsored and directed by the state with a prescribed social – political agenda and of a magnitude corresponding to the scale and spirit of modern times. In the Soviet Union the Agitprop and Proletkult public art programs are undistinguishable in purpose and intention from the objectives of the revolution of 1918. In the United States, during the Great Depression, as a New Deal program and part of the Works Progress Administration (WPA), designed to address unemployment amongst craftsmen and artist, the Federal Art Project (FAP) was formed. Founded in 1935 as one of five Federal Project Number One programs directed towards the arts, the FAP funded the visual arts as a relief measure to employ artists and artisans to create murals, easel paintings, sculpture, graphic art, posters, photography, theatre scenic design, and arts and crafts . The “sky views” of the metro in Moscow (Fig 8) and the stylistic and constructive characteristics of the Hoover Dam, for instance, is evidence of the application of art to the building of infrastructure, at a time still when the physical presence of the city is meaningful, despite the limits inherent in the state sponsored public art program project.

New Deal programs such as FAP, altered the relationship between the artist and society to the extent it consolidated the artist and craftsmen as a distinct and specialize profession with a unique set of skills, which could be deployed for the benefit of a particular public objective but, ironically, autonomous in the formulation of public space, per say. The New Deal program Art-in-Architecture (A-i-A) developed “percent for art”, a financial structure for funding public art still in use today. This program gave one half of one percent of total construction costs of all government buildings, and eventually all building of a certain size, to “acquire” contemporary American art for that specific structure or, significantly, a designated alternative site.

The disarticulation of public art from the manufacturing of public formal urban space allowed public art to function as social intervention and engage, particularly in America, themes of identity politics and social militancy in multiple forms of expression. Contextual art, relational art, participatory art, dialogic art, community-based art, activist art and new genre public art, to list merely a few critical practices in public art today, pursue forms of artistic presence in the public space which are concerned more it seems with the collective psychology of the city, so to speak, and less with the formal characteristics of public space.

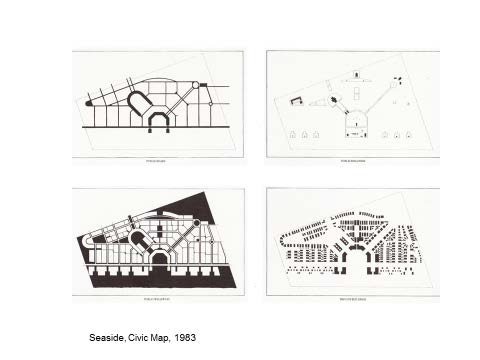

Civic Art, though, would have a direct influence in the formal thinking of American New Urbanist theory which promoted the critical reconsideration of Public Space in the “public space less” contemporary American city. In 1982, the implementation of the masterplans for the Town of Seaside in Florida and Battery Park City in lower Manhattan, was a committed recovery of the configuring and operation of public space as public art and while new conceptions of public art forms are not excluded, the urban design plans reintroduced the figure as a critical device in the formulation and articulation of the public realm as art.(Fig 9)The city today, characterize as it is by a diminish sense of the collectivity, in form at least, requires a renovated sensibility towards a definition of Public Art and the extent to which art can articulate, inspire and encourage the profile of the “new” Public Space in our lives. With the return of the “figure” should we be content with ethereal social space alone? Will there be again a project integrated as artfully and constructively to the infrastructure of the city as the Rockefeller Center in midtown Manhattan is, or will there be another construction of civic significance in the public realm as the extension of the public space and the erection of the Monument to the People’s Heroes in Tiananmen square in the years after Liberation? (Fig 10)

The Dashilar Project

“Peking, Has there ever being a more majestic and illuminative example of sustained town planning? ”, is an exclamation you one often reads from urbanists and scholars visiting the city in the middle of the XX Century. (22) The central axis, connecting the palace and the altars, is the fundamental compositional device that gives the city its relentless highly formalized structure. Dashilar, a district south of Tiananmen Square and built just outside Zhengyangmen, is exceptional for its distinct informal urban structure defined by an organic growth pattern which is in sharp contrast with the formality of the grid within the walls of the Imperial City. The district, which dates from the earliest days of the Ming capital and remains practically intact today, is tangential to the central axis, and, in history, presumably, at the margin, a spectator from the domestic realm to the yearly dynastic processions from the palace to the Altar of Heaven along the array of monuments the axis consisted of. The prosaic in tandem with the sublime, a Vitruvian ideal of the Public and the Private realms co- existing and inseparable, constituting the essence of the classical city, if the term is indeed applicable.

Within this picture frame of Beijing, “An unparalleled masterpiece of city planning”, in the words of Liang Sicheng who, writing in the early 1950’s would explain “Beijing is a planned entity… Therefore we must first of all realize the value of the wonderful structure which gives the city its intrinsic character. Beijing’s architecture as an entire system is the most intact anywhere in the world. This should be the point of departure and as a most extraordinary and precious work of art, it still retains its vitality and maintains its traditions.” (23) If this position is true, and on hindsight it certainly was, Dashilar as a whole is to be treasured. The domestic urban fragment that remains is so cohesive and integral that it is able to convey, in its distinct form and presence, a meaning and a narrative appropriate to it as an urban artifact and thus as a work of art. For “there is something in urban artifacts that renders them very similar, and not only metaphorically, to a work of art. They are material constructions, but not withstanding the material, something different: although they are conditioned, they also condition.” (24)

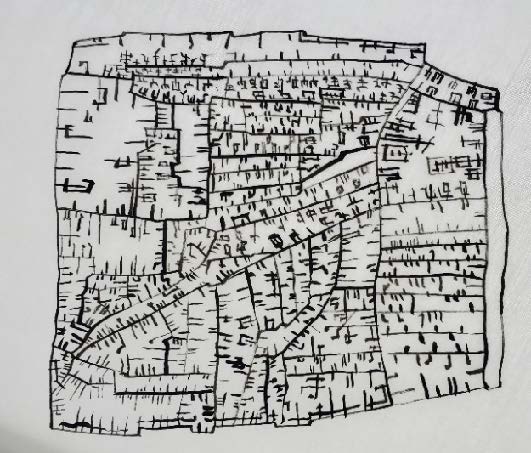

The street and block map of Dashilar drawn as a figure against a field or “ground”, reveals the inherently autonomous quality of the fragment. (Fig. 11) Extracted from its contextual setting and historical reality, as material culture, as an urban artifact, the figure of Dashilar, projects a definition and identity of its own. As with Henry James and “the figure in the carpet”, the urban fragment implies multiple readings and yet remains illusive, open to interpretation. Removed from its context in time and place the Dashilar fragment as a figure has the semblance of a disinterred archeological artifact, where the block and street pattern, discernable at a glance in the shape and geometry of the figure, reads as the shattered fragments of a broken vase, dusted, its shattered pieces evoking the whole.

“Break a vase, and the love that reassembles the fragments

is stronger than that love which took

its symmetry for granted when it was whole”.

( Derek Walcot)

Indeed the Dashilar figure ground drawing reveals an urban fragment richly textured by the passage of time and modeled from centuries old migrating patterns. Dashilar memorializes in its figure-ground the archaic paths of movement of people, from the old Yuan capital to the south gate of the Ming walls. (Dashilar Project) It is reminiscent of the perennial beginnings of towns, of foundational traces as one might see in the patterns of informal settlements today, characterized as they are by empirical and exigent organic growth, from necessity rather than liturgy. (Fig.12) The inaugural circumstances of these types of settlements, almost always “illegal” and most certainly outside the conventions of the official planning profession, determine early on and with conviction a consolidated urban figure which in tempore , if sustained and nourished, contributes critically to identity of place. Migration and circulation patterns, the natural conditions of the terrain and the casual comings and goings of common man, engrave upon the landscape, forever as in Dashilar, the in-print of everyday life and the dignity of the ordinary. Infrastructure and procession have in Dashilar an authenticity and elaboration that renders the street and block pattern with an expressive art content, itself singular an irreproducible.

This is perhaps the greatest “art value” of Dashilar, the archeology of movement of the urban fragment and it is this impossible to duplicate vernacular fabric, molded in time from human experience, that needs to be not merely preserved but reiterated by employment to insure Dashilar “retains its vitality and maintains its traditions. “The Art of Infrastructure is the Art of Public Memory. Infrastructure is often the most enduring trait of the urban fragment and its most resilient feature. Buried, silent, ignored by the idle by-passer, as with the Trajan’s Forum, infrastructure is all that is left in the space of the ruin, the last of the memories.

Dashilar, the topic at hand, is not forgotten though, it is not lost, quite the contrary, it is at the center of a polemic with broad implications on public art and the role of art in urban renewal politics and preservation economics, relevant not merely to the greater master plan of Beijing but with implications to towns and cities the world over. Under the auspices of the Shanghai Academy of Fine Arts, Shanghai University (上海大学上海美术学院), artist, curators, planners, architects, developers, preservationist, historians, community organizations, city and municipal authorities as well as individual voices, stake holders all in the prospect of Dashilar, convened in a series of symposia to discuss the “trend, modes of appraisement and criteria of public art” in Dashilar. The “International Public Art Study Workshop” conducted by Public Art Cooperation Center (PACC), of Shanghai Academy of Fine Arts and Public Art Magazine, undertaken by the Studio for Public Art Theory & International Exchange of the Shanghai Academy of Fine Arts, initiated a critical review of Dashilar titled, meaningfully, “Renewal Plan of Historical Blocks in Beijing Dashilan”. A reference to the fundamental formal infrastructural logic of Dashilar expressed figuratively in the street and block figure ground of the urban fragment.

In a redefinition of what public art might be today, consideration must be given to the reality and resonance, in the content of our built environment, to public infrastructure, too long neglected and removed from artistic expression. Art in Public Places in Dashilar, can, and perhaps should, be the Art of Infrastructure. Since the whole as an urban artifact, we argue, is Dashilar’s most remarkable expressive quality, a conception of infrastructure “according to artistic principles”, Camilo or infrastructure “artistically considered”, Louis Sullivan, could reiterate the whole and ensure its preservation and, most importantly, guarantee continuity as a “place for living”. Art in Public Infrastructure considers, as instances of infrastructure art, at least two interventions in the urban configuration of Dashilar, one above the surface of the street, the other below, one visible and one invisible, both the shadow of the fragment to be preserved and enhanced, and both committed to public service and in that sense constituting a form of Art of Wellbeing. The invisible “art work” is the completion of a waste management system for Dashilar, alternatively, the visible system, above grade, is a mini-transit system or N.O.T., Neighborhood Oriented Transit. A sewage main along the Hutong and a single lateral connection to the Siheyuan courtyard house replicates the prevalent pattern of street and alley to house in Beijing in general and specifically the street and block emblematic fabric of Dashilar.

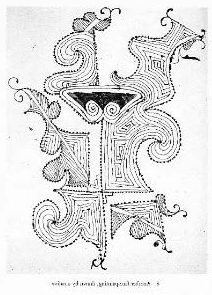

Street and block pattern of Dashilar as an emblem or Typos yields an identity of its own, at once local and universal. Given that it is shaped and formed from a tacit phenomenological response to time and social geography, the urban fragment while pertinent to all cities, is nonetheless bound to a place. Because it is circumstantial, it shares stylistic and constructive qualities with parallel vernacular art forms in terms of means of production, style and content. Conceptual studies of a sewage system in drawing form for Dashilar reveal the compelling and enigmatic dimension of the urban fragment as a work of art common to all as human experience, and a biographical quality in the production of the figure by the evidence of the “hand of man”. A drawing of an imagined “main and root” sewage system , drawn with calligraphy brushes made by Dashilar artisans, shares an accidental art quality with the induced crackling motives of Song dynasty Kuan ceramics, for example. (Fig.13) The sewage system pattern the drawing describes, derives its intricacy and complexity, and generic quality, by replicating the established timeworm hierarchy of street, alley and configuration of the courtyard in the block fabric of Dashilar, which, as is the case with the Kuan ceramics and the inconsistent impression on the clay from the heat of the kiln, is the outcome of predictable rational construction processes, and simultaneously, the result of the unpredictable influence of time on the molding of urban space. (Fig.14)

Amongst the stated objectives of the official Dashilar Project, is the enhancement of its infrastructure. (26) In Dashilar presently there is in an incomplete sewage management system in place and, surely to be taken into account as well, the remaining Ming network of pipes for waste water and flood control. A deserving ”state of the art” sewage management infrastructure is essential for the wellbeing of the population and to guarantee an assured future for Dashilar. The single lateral connection to each courtyard, the root connection, allows the Siheyuan to return to an either single occupancy, pre 1949 past, or continue as multifamily courtyards, made more convenient and comfortable with an appropriate and up to date sewage infrastructure. In the completion of a creative waste management system, the craftsmanship traditions of Dashilar could be employed in the fabrication of the infrastructure of the neighborhood, much of which, by necessity, would be done by hand, by masons carpenters and plumbers. The “Toilet Revolution” is National Policy, in Dashilar though, it is an opportunity for the reconditioning and adaptive-reuse of a significant, sizable and densely populated district, while simultaneously, weaving further the urban fragment in the greater fabric of the city and in the collective consciousness of its residents.

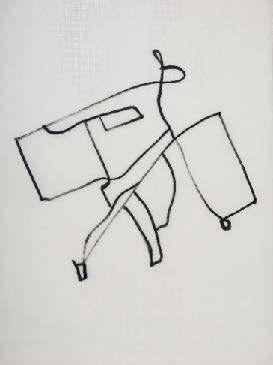

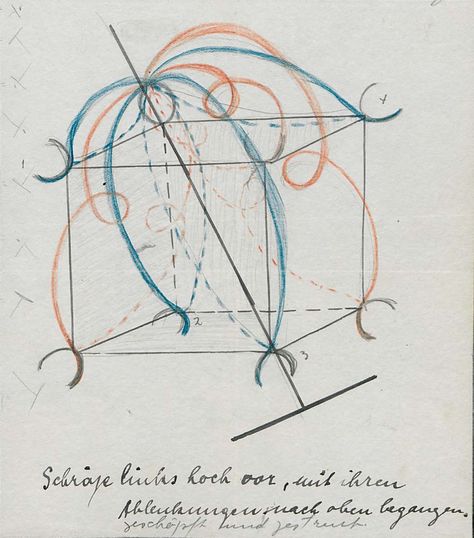

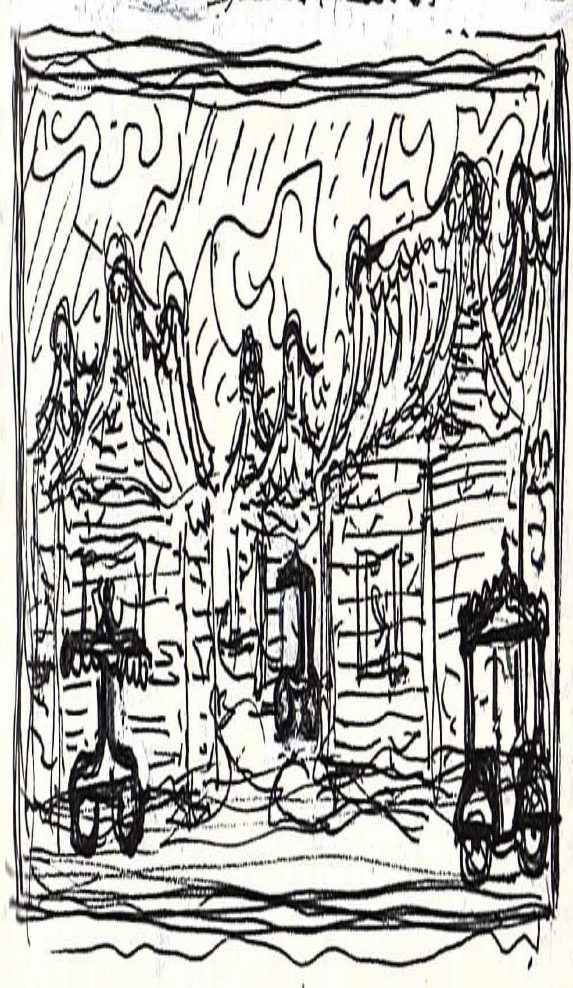

The visible Art in Public Infrastructure proposal is Art in Transit Places. A Mini Transit System, reiterates the inherent meaning of the urban fragment by means of a thoughtful and artful infrastructure, as is the case with the subterranean sewage system. The drawings of routing for a N.O.T. system in Dashilar reveal the kinetic aesthetic quality of the urban fragment, itself a product of movement in time. (Fig 15) The “circuit line” drawings of the trajectory of the public vehicle are reminiscent of Bewegungkunst drawings of Expressionist dance choreography describing movement in dance composition. (Fig 16) Prompted by the dynamism of the machine, modern art manifestos discovered means to articulate forms “of continuity in space” and ways to render speed and movement in poetry, sculpture and dance. Futurist, Dadaist and Cubist paintings and collages reflected the dynamism of an “engine driven civilization”. Ausdrucktanz, as an alternative to classical ballet, perceived then as static and stagnant, develops new drawing forms to express kinetographic dance composition.

The experience of a century of describing movement in art is useful in understanding traffic flows and transportation circuitry. Not merely for N.O.T. systems but for larger in scale transportation such as highway, rail, air and sea networks. Drawings for a transit system for Dashilar demonstrate a harmony between the urban fabric to be preserved and the introduction of movement. Given that one equates the other, the need for wholesale demolition and tabula rasa practice is averted. Conceptual drawings of routes show the course and directions of vehicles in response to street and alley dimensions in Dashilar and find natural realms newly defined by the movement of vehicles.

Whether a prescribed course and schedule system or “on-call” routing, Mini Transit Systems are complimentary to Mass Transit. They are implemented not as inter-neighborhood connectors but rather circumspect to single communities. They provide transit services within much more limited boundaries and can be more easily customize to address the particular needs of each neighborhood. These innovative transit solutions, being implemented by both the public and private sectors are the precursors to deployment of the automated electric battery platform, or fuel cell, vehicle and can provide a safe and more convenient transportation system at a micro scale in Dashilar.

The flushing toilet, and the correspondent underground infrastructure, will likely be replaced, in a not too distant future, by new water consumption and hygiene science technologies. The electrochemical reactor toilet breaks down water and human waste into fertilizer and hydrogen, which can be stored in hydrogen fuel cells as energy. (27) Similarly, of profound significance is the nonfictional advent of the interconnected – automated vehicle in Urban Design today. The car is undergoing a transformation from mechanics to computerization, as the wire line telephone was transformed and, for all practical purposes, eventually supplanted by the radio wave cellular smart phone. The ethernet protocol automobile will have an impact on urbanism in the dimensions of streets, for instance, or the necessity for parking, from the diminution, if not abandonment, of individual car ownership. There are close to a billion parking spaces in the United States, a gross acreage which in terms of a land use question alone, constitutes a radical paradigmatic change in city design. The driverless car will come in a myriad of sizes and models, performing as distinct functions as delivering groceries and providing the platforms for vehicles for mini transportation systems. (Fig 17) The machine population of Dashilar, like everywhere else, will be irrevocably changed by automated technology and the artificial intelligence of the Public Robot.

The little that is left of figural physical space will be affected irremediably, by the altered paradigms of transit and transportation when the already ubiquitous vehicle machine is no longer private nor directional but rather public and anonymous in the space of the city. Familiar machines, like the car, airplane or train, in perpetual motion, more numerous yet, systematic and, most enigmatically, automated and able to “think” for themselves. Will new technology, like the interconnected – driverless car, redefine what is public and will art be limited still to spatial considerations or will it insists on affecting our lives, audibly and visually more completely, and bring us back, to a Vitruvian ideal of the city constructed from a harmonious balance between the Private and the Public, where Art “walks amongst us”, as the automatons of Daedalus and Hephaistos?

Art in Public Robots is an Art in Infrastructure proposition. In fact, while the evolving technology in robotics is at first glance the result of science and engineering in applied mechanics, industrial design and logistics, in our collective psychology, the robot is introduced to our imagination through art in cinematography and science fiction literature. Robots are familiar and understandable to us as heroes and villains, compassionate and ruthless, sharing the virtue and vice of humanity, from the work of art. The robot Maria from Fritz Lang’s Metropolis represents not merely a feat of engineering but the mechanical means for political change in the dystopic and cruel city of the future. (Fig 18) For robots, as extensions of ourselves, and the extent to which they inhabit the public domain, will be decorated. Since time “in memorial”, man has adorned himself as much in search of beauty as to fulfill a dutiful need to address an obligation to the public and found no “difference between building and image making as far as usefulness is concerned” The face paintings of the Caduveo people, which like the Yanomami from the Orinoco basin live still to this day, in what to us seems a dreamlike Paleolithic existence in the forest of the Alto Parana, are conceived and composed for the public realm and in community “confer upon the individual his dignity as a human being; they help to cross the frontier from Nature to culture, and from the mindless animal to the civilized Man. Furthermore, they differ in style and composition according to social status, and thus have a social function”. (Fig 19) (28)

To the questions of “The Origin of the Work of Art”, Heidegger, or “What is Art”, Danto, the question of the where is public art should be added. Where is Public Art today, in urban “reserved space” only, sites officially designated by “organized art” entities for public art use, (Danto ) or does it pass us by reproduced on the side of a public bus, or do we hear it collectively in pop lyrics? Public space itself is radically different than in the traditional city, characterized as it is by the incessant murmur of the machine, yet remains, as it should, an integral component of collective life in the nebulous realm of social media and the internet. A redefinition of public art, likely less specialize and less constraining, follows suit in the age of connected devices and wearable technology.

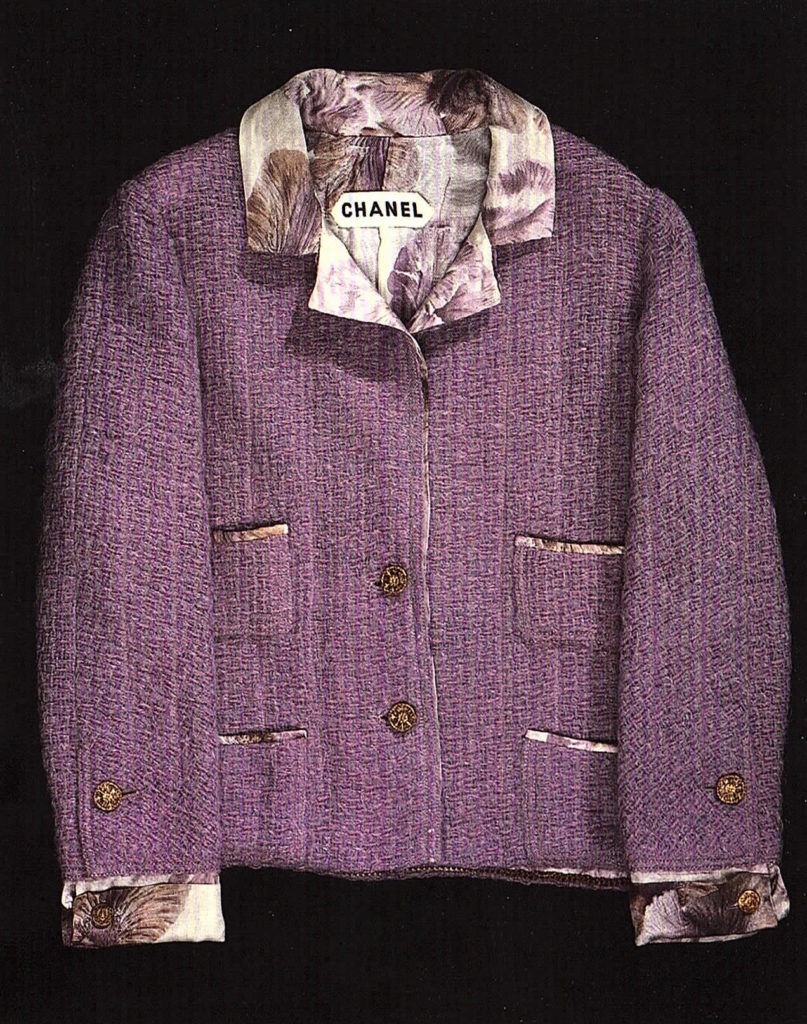

Modern art’s unrequited love for the machine finally resulted in the distancing of art from public life. The disdain of the avant-guard, in particular, for the expressions of mass culture exacerbated further the inability of modern art to contribute to public life and was eventually left behind in the huis-clos elitist confined realm of the gallery and the museum, recognized as art not by the “people” the modern movement was so passionately committed to serve as the “people’s avant-guarde”, but rather paradoxically, by committee, of the educated and the qualified in the form of “curatorial power” (30) So irreconcilable have art and technology seemed that many who believed in the creative discipline of form still cut themselves off deliberately from important areas of contemporary experience”. (31) In the critique of the relationship between “producer and consumer” in modern art theory there was no space for the art and craft of the practical, the useful nor of the ordinary. The composite dresses of Coco Chanel, therefore, designed as Art for Public use and as Art in Public Persons, so diligently and ingeniously knitted and woven in contrastive braiding and using industrial fabrics could not be recognized as art, despite its radical and liberalizing impact on women wear, from the corset to the light “piece” set, all together more fitting and comfortable to the modern work place. (Fig.20)

Is Art in Public Places today, as a program, more public than Central Park, or the Summer Palace from a century ago? Is the art that this subsidized programs promote more meaningful to a public consciousness which, more than ever in the history of mankind, is formed by the incessant exposure to all forms of creativity in popular culture. The turn of the century conviction of the demise of the “ aura” of art and the feared denigration of “high art” by mass production and “mechanical reproduction” in complicity with Capitalism destroyed the aesthetic, cultural, and political authority of art. The idea that “For the first time ever, images of art have become ephemeral, ubiquitous, insubstantial, available, valueless, free”, (29) and thus, as a consequence lacking the aesthetic authority of the original work of art, is at odds with a fundamental and profound meaning of art as a human instinctive and habitual act and to the notion there is no such thing as art but rather ” there are only artist” (Gombrich) (32) for “the true beauty where every century recognizes itself , is found in upright stones, ship’s hulls the blade of an ax , the wing of a plane.”(33).

The expressive quality of art, its poetic content as well as adornment capacity, has the potential to reach us in a way different from mere systems-programing in a palpably forma humana. The science of place and the archeology of movement, latent in the fragment of Dashilar, can be articulated by art, and, in the process, discern the critical elements which imbue a setting with a distinct character and, thus, identity. Art is an intrinsic value in the Dashilar of today and has contributed to the reevaluation of the neighborhood. Whether right or wrong, art has had a central role to play in Dashilar. Imposed or not, The Dashilar Project has been viewed in part, through the lens of art and artistic expression and whether it has been effective or not, public art has found a place in Dashilar. That it is somewhat removed and somewhat inaccessible, and perhaps, as well, from la vida cotidiana of the inhabitants of Dashilar, it does not mean that art cannot contribute to the wellbeing of the population. Despite the relative absence of intimacy with the reality of the neighborhood, the pertinence of artistic intervention is nonetheless welcomed, as it might be in a universal sense, relevant to all cities, and allows to construct a perspective from which all human endeavor can be engaged, for the building of beauty and comfort through time.

Across time to our days, in the theory and practice of city building, the public space is the ideal depository of public art due to a shared and common purpose in content and utility. Not all art is public, of course, but the art that is indeed public, will be placed, by definition and necessity, within the public domain, whether physical or ethereal. In the Renaissance, the relationship of public art to public space is changed irrevocably. Public space and public art is viewed then as a Gesamkunstwerk and composed as a singular entity where, statue, column or memorial are part

of a spatial configuration and perform an identical socio political program function, as is the case with the Campidoglio, where the performance of public art is of a mundane and utilitarian character as much as it might be of a celebratory or commemorative nature and in this sense recovers from the distant past the equation of art and infrastructure as one in the public domain.

What waste, what misfortune befalls the public domain of the city in the absence of public art to support it. For the sake of history, of cultural patrimony, for what makes us distinct and diverse as a peoples, opposed to the sameness that comes from a “generic” conception of the res publica, we must change. In western nostalgia for Scientific Materialism the celebrated phrase “All that is solid melts into air” (34) can serve, if nothing else, as a principle by which the century old destructive and counterproductive divorce between art and the everyday can be overcome.

Dashilar is indeed in evolution and in a critical chapter of its material history. If so then the social consciousness of Dashilar, the sorrow and joy, can be profiled through a creative eye and while the most pressing social concerns of Dashilar are unlikely to be resolved by art only, public or not, it should nevertheless offer a potential framework for the building of beauty, comfort and wellbeing. Art reminds us of ourselves, of what we are willing to forget in the anonymous mundane routine of the everyday. As it might have been in antiquity, can art, in our public psychic, be a companion in our journey to recover what we have lost and forgotten.

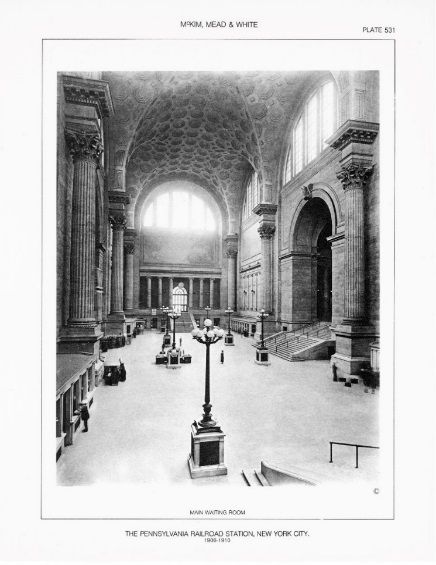

We can’t see the walls from Dashilar any longer, we won’t hear lamentations or cries of joy from the wall ever again, the walls are no more, their fate shared by countless cultural patrimony of human toil and accomplishment dismembered from the built and social fabric of the city, dismissed and disdained irreverently. (Fig 21) As with the “waiting rooms” of Pennsylvania Station in Manhattan demolished in 1963 under the unbearable weight of real estate speculation and an acute absence of cultural collective consciousness, in Beijing, the greatest infrastructural contribution to the city, belonging to all, renowned for its beauty and artistry, for lack of imagination in official planning theory devoid as it was there and everywhere else at that time of art and ingenuity, would pass us by, and “all this moments will be lost in time like tears in the rain” (35)

Fine, I won’t speak more

of the past. I’ll think only of us

here on the gate tower,

today……

White doves.

(did you know that they were white doves)

Flying before us.

Lin Huiyin Old Gate Tower, 1935

Teófilo Victoria, Adib Cure, Zhao Yizhou

Citations:

- E.H.Gombrich. A Little History of The World [M]. Yale University Press, 2005, 7

- The Cave of Forgotten Dreams. Dir, Werner Herzog. Per. Werner Herzog, Jean Clottes, Julien Monney Creative Differences, 2010, Documentary

- Lewis Munford. The City in History [M]. Harcourt Brace Jovanovich,1961,6-7

- Leonardo Benevolo. The History of the City [M]. The MIT Press1975, 145-147

- Frank Granger. Vitruvius: On Architecture [M]. Harvard University Press, 1995, 33

- Morris Hicky Morgan. Vitruvius: The Ten Books on Architcture [M]. Harvard University Press, 1914,16

- Vincent Scully. The Natural and The Manmade[M]. ST. Martin’s Press, 1991, 24

- Morris Hicky Morgan. Vitruvius: The Ten Books on Architcture[M]. Harvard University Press, 1914,17

- Joseph Rykwert,Neil Leach, Robert Tavernor. Leon Battista Alberti: On the Art of Building in Ten Books [M]. The MIT Press, 1988, 3 10.

- William L. Macdonald. The Architecture of the Roman Empire: An Introductory Study [M]. Yale University Press, 1965,78-79

- John B. Ward-Perkins. Roman Architecture[M]. Harry N. Abrams, 1977, 119

- Alois Riegl, The Modern Cult of Monuments: Its Character and Its Origin [J]. Oppositions, Rizzoli, 1982, (25):21

- Alois Riegl, The Modern Cult of Monuments: Its Character and Its Origin [J]. Oppositions, Rizzoli, 1982, (25):26

- Henri Pirenne. Medieval Cities: Their Origins and the Revival of Trade [M]. Doubleday Anchor Books, 1956, 39

- Henri Pirenne. Medieval Cities: Their Origins and the Revival of Trade [M]. Doubleday Anchor Books, 1956, 39-40

- George R. Collins and Christiane Crasemann Collins. Camillo Sitte: The Birth of Modern City Planning [M]. Rizzoli, 1986, 151

- Alois Riegl, The Modern Cult of Monuments: Its Character and Its Origin [J]. Oppositions, Rizzoli, 1982, (25):22

- James S. Ackerman. The Architecture of Michelangelo [M]. The University of Chicago Press, 1961, 163

- James S. Ackerman. The Architecture of Michelangelo [M]. The University of Chicago Press, 1961, 162

- Anthony Blunt, Artistic Theory in Italy, 1450-1600 [M]. Oxford University Press, 1994, 7

- Werner Hegemann & Elbert Peets. The American Vitruvius: An Architect’s Handbook of Civic Art [M]. New York: The Architectural Book Publishing Co, 1922, 1

- Werner Hegemann & Elbert Peets. The American Vitruvius: An Architect’s Handbook of Civic Art [M]. New York: The Architectural Book Publishing Co, 1922, 2

- Steen Eiler Rasmussen. Towns and Buildings [M]. The MIT Press, 1951,1-9

- Wu Liangyong. Rehabilitating the Old City of Beijing [M]. University of British Columbia Press,1999,10

- Aldo Rossi. The Architecture of the City [M].The MIT Press, 1989, 32

- Jia Rong, etal. Exhibitioon Publication:Dashilar Project [M]. Dashilar Project,2014, 60

- Peter H. Diamandis and Steven Kotler. Abundance: The Future is Better Than you Think [M]. FreePress, 2012, 97-98

- Claude Levy-Srauss. Tristes Tropiques[M]. Criterion Books, 1961,176

- John A. Kouwenhoven. The Arts in Modern American Civilization[M]. The Norton Library, 1948, 11

- Arthur C. Danto. The Abuse of Beauty: Aesthetics and Concept of Art [M]. Open Court, 2003, 104

- John Berger. Ways of Seeing [M]. British Broadcasting Corporation and Penguin Books, 1972, 32

- Primo Levy. The Periodic Table [M]. Schocken Books,1984, 179

- E.H.Gombrich. The Story of Art [M]. Phaidon Press, 1950, 5

- Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. The Communist Manifesto [M]. Penguin Classics, 2011, 68

- Blade Runner, Dir. Ridley Scott. Per. Harrison Ford, Rutger Hauer, Sean Young, Warner Bros. 1982, Motion Picture

Art in Public Infrastructure- Illustrations:

Fig 1. Cueva de las Manos, Rio Pinturas, Santa Cruz, Argentina, XIV Century BC PROGRAMA DOPRARA (Documentación y Preservación del Arte Rupestre Argentino) INAPL (Instituto Nacional de Antropología y Pensamiento Latinoamericano). Ministerio de Educación, Cultura, Ciencia y Tecnología. Argentina

Fig 2. Plan of Trajan’s Forum, Ink on Cloth, P.M. Morey, 1835

Fig 3. Trajan’s column, Vedute Dei Principali Monumenti di Roma Antica, Luigi Canina, 1851

Fig 4. Trajan’s column in the ruin of Trajan’s Forum (photo authors)

Fig 5 The David, Piazza della Signoria, Michelangelo, Florence, 1501

Fig 6. Equestrian Statue of Marcus Aurelius, Piazza del Campidoglio, 175 AD, Rome Equestrian statue of Marcus Aurelius. Artstor.

Fig 7. The American Vitruvius : An Architect’s Handbook of Civic Art, First Edition, 1922

Fig 8. 24 hour Soviet Sky, Maiakovskaia Metro Station, Alexey Dushkin architect, Aleksandr Deineka artist, Moscow, 1938

Fig 9. Seaside Masterplan Drawings, Ink on Paper, Duany Plater-Zyberk & Company, Miami, Fl. 1982

Fig 10. Monument to the Peoples Heroes, Liang Sicheng, Lin Huiyin, Chen Zhide, Tiananmen Square, Beijing 1952-1958 Beijing

Fig 11.Dashilar Fabric, Laboratory of Everyday Things, 2018

Fig 12. El Pozon , Figure Ground Drawing, 2010

Fig 13. Dashilar Sewage Drawing ( Callighraphy brush on Paper)

Laboratory of Everyday Things, 2018

Fig 14. Kun Ceramics, Song Dinasty, 960-1279

Fig 15. Dashilar N.O.T (Neighborhood Oriented Transit), Caligraphy brush on Paper, Laboratory of Everyday Things, 2018

Fig 16. Kinetography Drawing from Rudolf Von Laban, Basic Principles of Movement Notation, 1914

Fig 17. Dashilar View populated with Interconnected Automated Vehicles (Ink Marker on Paper), 2018 Laboratory of Everyday Things

Fig 18. The Robot Maria, Metropolis, Fritz Lang, Thea von Harbou, 1927

Fig 19.Caduveo Female Face Drawing, C. Levi-Strauss, Tristes Tropiques, 1961

Fig.20 Mauve tweed Jacket with double pockets. Gabrielle “ Coco” Chanel, 1964

Fig 21. Main Waiting Room, Pennsylvania Railroad Station, Manhattan, Mckim Mead and White, 1906-1910